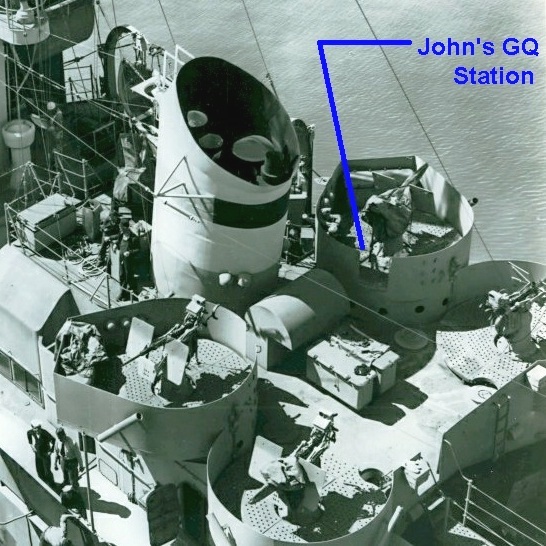

GQ Station

Full time duty on board ship found me in the radar shack, and those duties were outlined previously. However, when general quarters was sounded (that's the alarm which means "everyone man their battle stations!"), my duty changed to gunner on a 20MM cannon [Ed. Note: Link is to an official US Navy Ordnance document] which was located amidships on the starboard side on the deck above the main deck, and to the rear of the stack slightly.

Ship here is the USS Lake (DE-301); cropped/edited version of a US Navy Photo.

The gun crew on that weapon consisted of a gunner, loader, trunnion operator and a communications man, the one who wore the headphones which were connected to the central system. The gunner on this gun was also the man in charge. This was not the case on all types of guns, however.

The loader's responsibility is pretty obvious, to "Slap another magazine onto the cannon (don't know what it was attached to is properly named) immediately" and "keep 'em coming!" I'd always thought there were ninety rounds in a magazine, but I've heard others say it was less than that—something like seventy or so. But when I recall how quickly they were expended, I still feel it was more the way I thought it to be. [Editor's Note: According to US Navy OP No. 911 (link above), the magazine for a 20mm cannon contained only 60 rounds, even though it had a firing rate of 450 rounds per minute (or 7.5 rounds per second). In only 8 seconds of continuous fire, you'd need another magazine! With a maximum range of 4800 yards at 45° elevation (so to be effective, a target would need to be much closer), it was often said, "If you hear a 20mm firing, it's time to hit the deck."]

The rounds in the magazine sometimes misfired or hangfired (I can't say I know what the difference is right now), or just didn't explode or expend from the shell in which housed. Sometimes the detonator wasn't hit properly by the firing pin, and other times it was and still didn't "go off." [Ed. Note: See Chp.17,Footnote 4]

Tracer rounds were spaced every so many rounds apart. They gave a lighted path to the target so the gunner could adjust his line of fire accordingly. Most often gunners failed to "lead" their targets sufficiently to be effective, aiming and firing right at the target (especially true of aircraft). By the time the rounds would reach the position at which the aircraft had been, the plane was no longer there. Leading the target meant firing at a point of an anticipated meeting of rounds and plane.

Thinking of the school at Miami at the Submarine Chaser Training Center, that resonant voice came echoing to my mind, "It can go off at any moment! Treat it with respect, and treat it hurriedly. Your life may depend upon it!" The gunner was responsible to remove those misfires and hangfires from the breach and quickly dispose of them over the side. I never forgot that warning, and I got rid of such shells in the manner prescribed—though always fearing the "possibility."

The trunnion operator's job was to keep the gunner's legs as straight as he could by raising or lowering the height of the barrel as the gunner pointed it up or down as was required to stay on the target. The trunnion operator turned a crank (circular and made of metal) which accomplished this raising and lowering.

The communication's man wore earphones plugged into a jack which gave access to a central control where orders for firing or "cease firing" came. During the Okinawa battle, I listened in on some of the conversation on the phones (in times of a lull in the battle), and it shocked me. Sailors knowing there were too many on the circuit to be identified, often told the officer giving orders where he could go and what he could do (sort of "getting it off one's chest"). That same M.O. existed on radios tuned to aircraft and land forces. There it was much more intense and tainted language, even downright filthy, crude and offensive.

The last thing I have to say about my gun and other gun emplacements is that they were surrounded by a circular sheet of metal, much like a turret without a top. I'd say the height was approximately four feet. This gave some protection, but not a great deal. Whatever protection it gave or didn't give, it was kind of a "blanket to cling to."

Whenever under way, anything which was spotted floating on the surface was considered a potential danger. Everything seen was considered to be a mine with the ability to destroy, so it wasn't unusual that we often were called to GQ to fire at many such objects—after it was carefully determined the objects were not humans afloat on a raft or actually in the water. All such calls to GQ came as a treat to take me from the radar shack (if on duty) and out into the fresh air and the ability to see what was going on outside. Firing at those objects presented a challenge and seemed more like sport than the serious business it was.

Since we were one of the older Destroyer Escorts, our heaviest armament was 3-inch 50 guns rather than the more conventional[1] five inchers. When still a seaman I'd been given the chance to be a first loader on one of our 3-inch 50's. I did pretty well with it while standing anchored (practicing) somewhere, but when under way and in heavy seas, that job became another story.

A line of men passed the shells (pretty long ones at that) along to the first loader, coming from the ammunition locker below decks. The first loader then put his left hand under the front part of the shell and his right hand behind the back of it, using that hand to virtually "throw" it into the breach of the gun. One problem[:]

As the ship pitched and rolled in heavy seas, finding that breech in which to throw that shell and then to cleanly insert it without jamming it into the metal which surrounded the breech, was most difficult. Knowing I'd been told that it was possible to explode a round by hitting it right on the nose, I soon decided that job would be done better by someone who was taller and stronger (and who didn't care about the danger involved!).

Rough Seas and Storms

When performing screening duty for convoys in rough seas, there were times it got so bad we had to leave the convoys in order to stay afloat. Those vessels weren't likely to be attacked by subs in such waters. But we needed to change heading right into the storm to keep from capsizing...and that course would often not be the course the convoys of heavier and more stable vessels were following.

In those kinds of storms we'd find ourselves at the very peak of a gigantic wave, looking down at what looked like valleys below at the lowest part of the water. Then suddenly we'd be on our way down, the water displacing what had been an empty space faster than we could ride it downward. That led to a tremendous crash when ship and water met.

While the dropping into the hole was taking place with no water to support us, the ship's propellers would pick up speed due to the lack of resistance of the water and spin wildly. The propeller shafts vibrated violently and shook everyone and everything in and on the ship! If you've experienced earthquakes of a fairly high Richter Scale magnitude, you have some idea of what that was like on board.

Whether on duty in compartments within the superstructure of the ship or below decks, you were bound to end up bouncing against bulkheads if not holding on to something immovable.

All topside duties, such as bridge watches, would be canceled in such storms, as water sprayed clear across the highest part of the ship onto the bridge. The small ports at the bottom of emplacements which were there to allow water to drain couldn't handle the volume. As a seaman I'd been on the bridge when it had to be abandoned because of that very circumstance.

Moving between fore to aft quarters, if done at all, would be attempted from the deck above the main deck, and even then one risked being washed into the raging sea when attempting it.

To try walking on the main deck meant suicide. Some of the gear which had previously been made secure became damaged or lost in those seas, so a sailor would have had no chance to withstand the force of the water and wind. The hardest sailor on board, whoever that may have been, never tried that bit as far as I know.

Oftentimes we thought of ourselves as being worthy of air, sea and submarine pay because we spent so much time in all three positions on and in the sea, and in the air as well. That didn't change our pay scale, but it made us feel we deserved to be able to brag a little about it.

In one such storm our ship listed (tilted) 67 degrees[2]. If picturing that ninety degrees would have put us parallel to the surface of the water, you can see we didn't have that far to go. It isn't hard to still recall that list!

For some reason I'd been topside on the upper deck, perhaps going to or from a duty station when that list took place. My concern was, "From which side shall I jump into the water? If I go over on the deck side, maybe I'll be swallowed up in the suction caused by the sinking. But if I try going over on the other side, I'll merely be jumping onto the hull, and it's a long way from the deck level to the keel."

In reality a more reasonable choice would have been to stay with the ship, for it would have taken open hatches or cracked seams to allow the water inside the ship to sink it. It probably would have floated like a cork until another smashing wave tilted it back into an upright position. All hatchways would have been closed tightly, as orders would have come over the P.A. System, "Batten down the hatches fore and aft!" This would have happened when a stormy sea formed.

Those stormy seas caused perilous times and must have rattled minds of everyone aboard as to their safety. In reflecting upon those times, I realize God in His grace, love and mercy was giving every man on the ship another opportunity to settle his spiritual destiny with Him before entering into eternity.

Food?

From storms we now switch to "chow time" or meal time. Various types of meals were served on board. I'm calling them "meals" out of respect to those who prepared them, not that the food served actually deserved it. But the cooks and the baker did the best they could with what they had.

If you knew what day it was and which meal of the day was to be served, you knew exactly what to expect. In my case it became "Which of those lousy meals will I consider eating in order to stay alive?" Most of them made me sick to think of them.

Any breads or bakery-type goods were baked with small bugs inside them. I think what happened was that the larvae of the bugs already existed in the flour, and the dampness of the sea, the South Pacific particularly, helped incubate them. They were so tiny, they couldn't be sifted out of the flour, so they were baked right in.

From there it was simply a matter of holding your bakery goods up to the light to show where the dark spots were, and then to pinch them out, and then continue eating as though nothing had happened. Yech!

The next entree of wonderment was the "green" eggs. What they were was some kind of concoction which may have had some eggs in it as a base, but they were a powdered substance to begin with. The green and slightly yellow mixture wasn't bad enough, but they had an awful odor as well.

Maybe in jest you've heard servicemen (very few women in the military in those days) speak of SOS. That for the most part wasn't referring to "Save our ship!" It meant "s--- on a shingle," a terrible way to describe any food. It was a whitish gravy sprinkled with beef chips, and the gravy would probably have served just as well to hold loosened metal parts together—not that the "aroma" given off by it was anything to brag about, either.

And, coffee! Well, that's what it was called. It had a taste of chicory, a plant whose root is used to "flavor" coffee, or, as my one dictionary states it, "to adulterate coffee." That sounds like a more appropriate designation.

Now, the coffee didn't already taste terrible enough on its own; they added saltpeter to it (a military-wide usage, most likely). Saltpeter[3] is a salty mineral used in the preservation of meats, basically. How it came to be known as an inhibitor for sexual desires among males, I don't know. [Editor's Note: This is a myth. The 'story' may even go back earlier than the WW-I era.[3]] But that's what we'd been told. As a matter of fact I recall that same story being told when I was in the CCC years before.

Mutton Party

Worse than any of the food or drink items mentioned thus far was mutton. Some dictionaries call it "the meat from 'mature' sheep." How true! By mature, they mean to say "very old" and "very tough" and "very odoriferous." That latter description can't be said to have been improper. It was the main feature of that stuff!

How awful did it smell or "stink"? When it was cooked on board, the odor clung to the bulkheads and any and all other surfaces exposed to it. There was no way to disperse or dispel those fumes. Amazingly, when looking at the cooked mutton, it looked as though it'd be very tasty. Don't be fooled by "looks."

If I live to be a hundred (not likely) I'll still be able to recall an incident which took place off New Zealand dealing with mutton.

For some reason we'd anchored way out from shore when there. The idea of stopping at all was to take on supplies, mainly mutton, a plentiful commodity in that country. The whale boat and its crew made the trip in and in time were headed back to the ship. En route to the ship, the guys got the idea that if they'd just toss the mutton over the side, they could say it slipped out of their hands when moving it in the whaleboat. It was frozen and could easily have happened that way.

On their return, the officer of the deck informed the skipper of the "tragic" accident and the loss of the mutton. The skipper, being the logical person he was, sent the whaleboat crew back to recover the mutton—adding his warnings of their misdemeanor. You see, the skipper was wise enough to know that frozen meat of any kind will not sink, just float in the water. "Nice try, guys!" everyone on board said of that crew in their valiant effort, as they headed back out to recover that dreaded supply of mutton.

Too Much Chocolate

Since the subject of foods is still prominent, here's a tale you may not want to read if you have a weak or queasy stomach or if you find bodily functions (or lack of them) repulsive.

From my prior statements about what was available to eat on board, and from the way I described those "foods," you might know I didn't eat any more of it than I had to in order to stay alive. What I had learned I could do was to store up a bunch of chocolate bars from the ship's store (when they became available) and to snack on them in place of a meal. [There's] one thing wrong with that, though![:]

The chocolate bars had some kind of additive in them to help preserve them from melting and from spoiling in the Pacific heat and dampness. I'd always heard it was some form of lead[4] which was in them, though today it seems this is said to be very toxic to the human system if ingested; so I can't be sure what the ingredient was.

Hot chocolate from the radar shack and chocolate bars from the ship's store became my mainstay in place of many meals, especially in place of those I knew I couldn't even think of, let alone tolerate.

In time these meal supplements or replacements began taking their toll on my digestive system. I noticed I didn't have bowl movements very often, and at that last stretch I'd gone something like seven days without one. Soon I began to feel very miserable when trying to force an elimination process to take place, but it just wouldn't happen.

Sick bay was a place I stayed clear of completely, but it was the only possible place left at which I could seek advice of what to do. The chief asked me some simple questions about my eating habits and the frequency of bowl movements (after I'd explained what was wrong). When he learned I'd gone seven days without, he told me I was very lucky I hadn't died, as few can last that long.

The procedure to remove the blockage may have been close to "hammer and chisel" surgery, following drinking down heavy doses of laxatives and oils. It seems removing the hardened material felt something like a woman must feel when delivering a child. It did eventually, after much pain, result in a successful conclusion.

After that I learned it was necessary, like it or not, to put down some of that chow in order to avoid another visit to sick bay and that unpleasant ordeal.

An Alcoholic

While in the area of ad nauseam food stories, here's one that deals with drinking—not water.

We had a first class Motor Machinist, or maybe he was a chief, on our ship who had to be in his forties already. He was a regular navy man who never shaved or appeared to be very clean—though that crew did work in hot, dirty surroundings. His weakness was alcohol. He'd drink absolutely "anything" with any alcoholic content, even hair tonics or after-shave lotions.

Some drinkers eat hardly any food to speak of, but this guy ate and drank. This presented a big problem when he'd previously drunk some of his concoctions which were not manufactured for that purpose.

A number of times I'd seen this guy expel the poisonous stuff from his body. Along with the junk he'd drunk, food just eaten would come up and decorate the deck where he stood.

On one occasion he'd just come up the ladder from the engine room and let it all go right there in front of me. As if that wasn't sickening enough, he'd evidently eaten a lot of fruit cocktail (don't know where he got it), and it sprayed all over the deck. Pieces of pear, cherries, peach, et al, it was all there to view, like it or not. My queasy stomach did a couple of flops, but fortunately I ate very little the previous meal.

Fear & Paranoia

There was one officer (that's a safe way to put it) on board who wasn't the friendliest person in the world, and his reputation earned enemies for him. There was one time when he'd probably wished he had displayed a different kind of image.

Officers when serving as "Officer of the Day" carried a sidearm, a forty-five semi-automatic weapon. This guy's weapon came up missing one day, and he was sure someone was out to get him; and maybe someone was for all I know. More than likely he was just over reacting, however.

It troubled him so much that he made a big fuss about it to the Skipper, who, wanting to dispel this guy's fear, called general quarters. The idea was to get all the men to their battle stations, thus leaving all the living compartments free of any noncoms so a thorough search could be made to see if the weapon could be located.

All the officers participated in the search, yet it took quite a long time to complete it. No weapon was found... which still didn't mean it wasn't hidden somewhere.

If the forty-five had been stolen with the intent of using it on that officer, the sailor who did it either dumped it over the side or hid it very well. If that was the case, it may be, too, that he had some forewarning of the search.

When I think of the dark, rainy, stormy nights where it was still possible to walk the decks, it would have been very easy to dispose of that officer if someone had it in mind—even without firing a weapon to carry out the plot. Just a smack on the head and a shove over the side, and he'd be long gone before anyone would have any idea of what happened to him.

From what I can recollect of that episode, the officer who feared for his life for quite some time, changed his way of dealing with the men. He wasn't taking any chances!

Don't play with a Loaded Gun!

In port one day, the Officer of the Day—a commissioned officer—and a petty officer were standing duty at the gangplank as was the custom. The commissioned officer had left for a time leaving the petty officer alone. Since there wasn't much going on, and dullness had set in, the petty officer began playing cowboy with his weapon, spinning it around on his finger. The gun went off as the rotation of the spinning found the gun aimed right at his foot when it happened. The expended round went right through his foot and the deck itself, entering into the engine room area.

Luckily, no one in the engine room had been near to the place of impact of the round, though the petty officer didn't feel very lucky. He was taken to either a base hospital or to a hospital ship in the area. In my notes I listed his destiny as "never returning to the ship again." I'm not sure about that as I think about it.

Movies

For a time, I acted as the ship's projector operator, the one who showed films on the fantail when we were in port and when films were available for exchange. It didn't require a college degree to operate the equipment, and it gave some prestige. The equipment consisted of both 16mm and 35mm projectors and a splicing machine. That machine was used constantly. The films we picked up had been used time and again, some being quite old to begin with, so it was inevitable there'd be breaks in the film while showing it.

When that happened, the entire audience of enlisted men (and officers, too, on occasion) let out a howl of disdain, blaming the operator (me) for the delay. The splicing sometimes took quite long periods of time to complete, and the crew became almost unruly. Hearing all that while trying to hurry the splicing only made me more nervous and less efficient, causing further delay.

Then there'd be the times it'd rain when well into the film where one would hate to have it end right there. But if the rains persisted, oftentimes it meant the movie for the night was over. And that same film might have to be returned to the place it'd been borrowed or exchanged. So the endings would never be known. That didn't set very well with the men, and somehow I got the blame—for even the weather.

In time I figured the prestige earned (you'd never know it gave any) wasn't worth the aggravation, and I gave up the job. That ended my career as a movie operator on board ship, but the stress ended as well.

Legs

In the months I'd been a seaman, and also while a radar man, I spent many hours on the bridge. Since all of that time wasn't duty time, there was an opportunity to just look around the decks below. In daytime hours sailors could be seen walking all over the place, though because of the gun emplacements which surrounded them, the view to the deck would be cut off here and there. So all one could see would be a pair of legs going by.

If it'd been my personal choice (in that day), the legs would have been those of females rather than men. But men were all we had on board. So we looked at legs to try determining whose legs belonged to which sailors. We got so good at it, in time we could determine the identity of any sailor on board.

I'd never before or since done a study on "legology," how it was possible to know who everyone was by his walk; but as sure as I am there's a God in heaven, walks are as distinctly different as fingerprints. Whether it was a shuffling, long or short step, bounce, dip, bowlegs, or whatever that made the distinction so certain, I don't know. I only know that of around upwards of 160 to 170 men on the ship, there wasn't one who couldn't be identified that way.

When out of the navy and relating that story, responses were received most often with "don't you believe it" facial expressions. Whatever was thought, I know that's the way it was!

Ice Cream and Better

A destroyer escort was not one of the navy's larger vessels, though it was close to the size of the older destroyers. So it didn't have the extravagances of ships such as cruisers, aircraft carriers, wagons [apparently how his buddies referred to battle-wagons, i.e., battleships], etc. By extravagances I mean the ship's store supplies, the better foods, barbers, etc.

One of the things many of us missed most was ice cream—available on larger ships. So when we were anchored or docked in the vicinity of those ships, we'd often try to go aboard to get some. One ruse utilized often was church attendance on those ships where chaplains were part of the crew. Hardly anyone would be denied a liberty for that purpose, unless on duty.

Some really had the genuine desire to attend a church service, while others just used that as an excuse to leave the ship. Both probably had the thought in mind of trying to get some ice cream while on that trip. But it often happened the line was so long, by the time you'd get to the door, the supply would be exhausted already or the equipment failed which produced it.

To show what the chances were of getting ice cream, in all the time I was in the Pacific, there couldn't have been more than two occasions on which I was successful. Indeed, I did always get the better of the two things for which I'd left the ship, and that was the church services! Specifically, the Word of God!

Cans, Subs and Sonar

I briefly touched on depth charges and hedgehogs previously. Yet I only scratched the proverbial "surface" in that description.

As an anti-submarine weaponry, depth charge attacks had to be a sub's greatest fear. Shooting the cans off the [K-guns] over the sides, while rolling the cans off the fantail [and launching hedgehogs forward of the ship], set up a pattern which was circular. If the depth at which the charges were set to explode was anywhere near to the depth of the sub in the waters below, they could prove fatal to the sub crew.

First, the [K-guns] were a Y-shaped metal tubing (it appeared that way) onto which the cans or depth charges were attached. There was an explosive which fired the cans well out over the sides of the ship. The reason for not rolling the cans over the sides was obvious—long rails leading to the sides would block passage on the deck. But even so, rolling them off wouldn't give the circular pattern needed.

The fantail, on the other hand, had plenty of room for the racks or rails to be installed without interfering with any passageways, the ship's forward motion also providing distribution away from the ship.

Earlier I explained how the ultimate explosion of the cans (especially if set at shallower depths and if our speed was reduced) would literally raise the fantail right out of the water. Naturally, an enormous explosion would also have the effect of vibration on the ship, and no one on board—no matter where located on the ship at the time—could mistake what had taken place.

When "arming" the charge, it was set for certain depths and the detonator would be activated at the same time. The detonator is the small explosive which sets off the [much] large[r amount in the] can or charge.

You can imagine what pressures exist in the waters of a sea [or ocean]. Untold tons upon tons of water weighted against whatever is under it. When a depth charge went off [anywhere near to a submarine's hull, the added force of that explosion (due to a shockwave through the water, or the explosive gases themselves) to the already existing pressure of the water could cause its hull to crack open, resulting in an "implosion" and the sinking of the sub.][5]

Sub skippers often used ploys to give the impression they'd been sunk by blowing garbage, trash, mattresses, oil and other debris out of their torpedo tubes. When the sub-chaser above would spot such "clues," all too often they gave up on the sub as having been sunk...when in reality it probably was quietly resting below soundlessly. I'm sure you've seen movies portraying that very scene.

Our skippers for the most part were not caught up in such trickery, and the continued dropping of the charges persisted until it was determined nothing could be heard on the sonar equipment anymore, or if definite signs indicated a hit. One of the most certain indications of a hit would have been floating bodies of the enemy.

By the way, the sonar equipment played the most significant part of our job by giving us an approximate location and depth of anything which sounded like the "ping" returned had bounced off a metal surface. All the equipment amounted to is the sending out of a sound signal which would return to the equipment and the operator's headset if it bounced off something.

Yes, there were times when in shallower waters we dropped charges on schools of fish, sunken ships, etc., which gave an indefinite signal. That was using the "better safe than sorry" theory, though it did become pretty obvious when the "enemy" turned out to be those schools of fish; for they'd be seen floating all over the place either stunned or dead.

At Guadalcanal and other such battle areas, from earlier parts of the war, where many vessels of both our own and the enemy's had been sunk, it was quite common to get a signal off a sunken ship and to treat it as a live sub. There was really little other alternative. And GQ, depth charge drops, standing at our guns, became as common as taking a shower or going to chow in time.

Chapter 18 |

TOC |

Chapter 20 |

Footnotes

1[Return to Text] The author's ship, being one of the first DEs built, had the smaller 3-inch/50 guns, but what mattered more than when a DE was built, was its class (or design). All DEs from DE-1 to DE-50 were Evarts class ships. The first DE to have 5-inch/38 guns was the USS Rudderow (DE-224; commissioned May 14, 1944). But the US did build more Evarts class ships after the Buckley (DE-51), Cannon (DE-99), Edsall (DE-129) and John C. Butler (DE-339) classes: DEs 256 - 280, 300 - 315 and 516 - 530 were all Evarts class ships. This page lists all of the DE classes and each ship, and here they are each listed by class and shipyard. It should be noted that DEs of the same class could have some differences, being built in various shipyards along both the east and west coasts as well as the Gulf.

2[Return to

Text] This particularly steep roll ("67 degrees") may have occurred only after being hit by a single larger than normal wave for a typical storm, or possibly while running parallel to or away from the edge of a typhoon. For example, in December, 1944, off the Philippines, some ships of the Third Fleet had even greater lists; though 3 Destroyers (Hull, Monaghan, and Spence) sank: On the USS Tabberer (DE-418), they recorded a 72-degree roll but recovered, and on the Dewey (DD-349),

one report states: "...our roll had increased to a consistent 65°, and several officers personally witnessed the inclinometer needle bang against the stop at 73°." And even this: "On several occasions, the starboard (lee) wing of the bridge dipped under and scooped up solid green water! None of us had ever heard at a ship righting herself from such a roll—but this one did!"

Reference: Pacific Typhoon, 17-18 December 1944.

3[Return to Text] Saltpeter is a common name for Potassium Nitrate (KNO3); which is one of the primary ingredients (along with charcoal and sulphur) of gunpowder. Although used as a preservative prior to the last century, that aspect was largely replaced by Sodium Nitrite (NaNO2) in the 1900s. The online edition of Britannica notes: "Its alleged value as a drug for suppressing sexual desire is purely imaginary." [See Saltpetre] And various 'urban myth' sites echo this fact as well. Military commanders certainly would not want to dose their men with something proven to have harmful effects.

4[Return to Text] Incorrect. The "additive" to keep these "military chocolate bars" from easily melting would have been oat flour (see ingredients below). Perhaps our author heard or read there was some lead in chocolate (it is a very tiny amount for most chocolate; read note about lead under Negative Health Effects here; there are Positive effects as well), and simply thought this was what kept it from melting. What our author ate must have been the Hershey "Tropical Bar" which had a slightly better taste than the original Army D ration. Its ingredients according to Hershey would have been: "Chocolate liquor, skim milk powder, cocoa butter, powdered sugar, vanillin, Vitamin B-1 and oat flour."

5[Return to

Text] At this point, the author made a completely false statement, that holes were made in submarine's hull because of a "vacuum" created in the water by a depth charge that had to be filled immediately. His words included: "...a hole would literally be "pulled" from the side of the sub." First, the highly pressurized gas bubble caused by the explosive charge is definitely not a vacuum! It takes just as much pressure to expand those gases as whatever amount the body of water is pressing against it with. And the fact is that bubble of gases expands very quickly in size until its pressure becomes equalized with the hydrostatic pressure of the water surrounding it.

Then, a short time later (but much slower than that of the explosive expansion), that pressure decreases and the bubble's gases become thousands of tiny bubbles or disolve in the sea water around it. It's possible our author was thinking of sea divers needing to use gas mixtures for breathing and not being able to surface quickly without getting the bends (or decompression sickness) and requiring a hyperbaric (recompression) chamber to prevent them from serioius illness or death.

However, submarines are not made of rubber, but rather a very thick and strong rigid structure, most often with a sea level atmosphere inside them (far, far from the pressure being exerted against the hull from outside it). Perhaps like some, the author was confused about the vacuum of "outer space;" thinking a vacuum somehow exerts a sucking force on anything out there. Wrong! The reason a balloon expands the higher it rises (and usually explodes) is due to the pressure inside it (and the weakness of the material to contain it) without the same amount of air pressure pressing against it.